The History Of Striking In Britain

Jun 15 2017

Darren Best

The act of striking is a form of protest towards an employer due to unsatisfying pay and/or working conditions. Striking has been observed as far back as Ancient Egypt, and has existed throughout history, across the world. Striking became a common feature of society during the industrial revolution, whereby people moved into the cities to work in manufacturing industries. A collective conscious developed over workers’ rights, poor conditions and wages. Workers began to stand up for their rights against business owners. Towards the end of the period, Trade Unions were legalised as a way to reform socio-economic conditions for British workers. This led to the creation of the Labour Representations Committee, which developed into the British Labour Party today. Over a century later, it is still not unusual to turn on the news and hear about an impending or ongoing strike. This year commuters in London witnessed the striking of transport in London workers due to job cuts and wage disputes which caused severe disruption and costed the economy an approximate £500 million, due to lost productivity. It might feel as if there is always an ongoing or impending strike, yet the numbers of those taking industrial action are lower than ever.

Striking in 2016

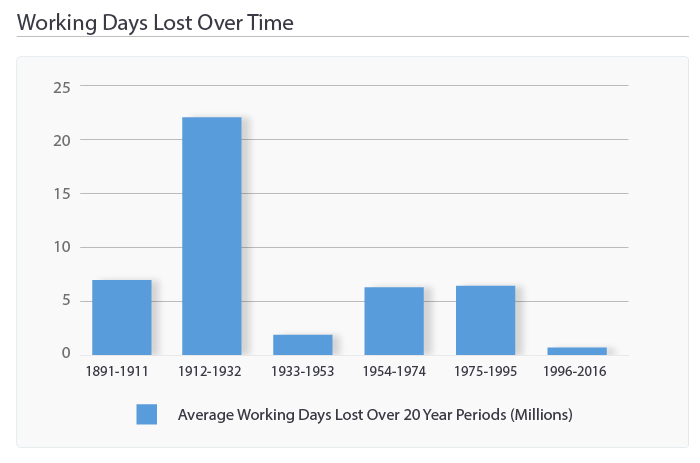

In 2016, 322,000 days were lost through labour disputes; an increase of 152,000 from the year before (170,000). This is primarily due to the Junior Doctors strikes which saw large-scale strikes across the country and accounted for 40% of days lost. This number, although seemingly high is actually the eighth lowest since records began in 1891. Industrial disputes have become far less common than in the past.

Credit: John Gomez/Shutterstock

History

1912-1934 was the period with the highest amount of working days lost. This is due to a few wide scale strikes including the 1926; the General strike which involved 1.9 million strikers and lasted 9 days in the UK. Those in mining and manufacturing protested over poor levels of pay and working conditions. The strike was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress, in an attempt to prevent wage dropping and worsening conditions for miners. This is followed by the 1921 Winter of Discontent where there were widespread strikes by public sector trade unions demanding pay rises following the Labour Party pay caps. The other years (1972, 1974, 1974, 1984) all account for various miners strikes. In 1974, strikes lead to a declaration of state of emergency, and a 3-day week was temporarily introduced to save electricity. Black Friday was another strike over pay and long working hours and strikes to prevent the closures of the mines throughout the 1980’s. In the 1980’s Margaret Thatcher’s government closed the majority of mines, leading thousands unemployed. This caused outrage and widespread striking. Although in the past 30 years we haven’t witnessed strikes on the same scale, we still notice peaks in the graph where relatively high numbers of people are striking. In the past 15 years, 2011 saw the highest number of days lost through striking. This was due to 1.2 million public sector workers striking during the peak of the European financial crash, where unemployment, cuts and redundancy rates sky rocketed. Industries that had more working days lost per 1,000 employees in 2016 were Education (39) Human health and social work (33) mining, quarrying and electricity, gas and air (16).

Reasons for WDL across industries

Credit: Juan Aunion/ Shutterstock.com

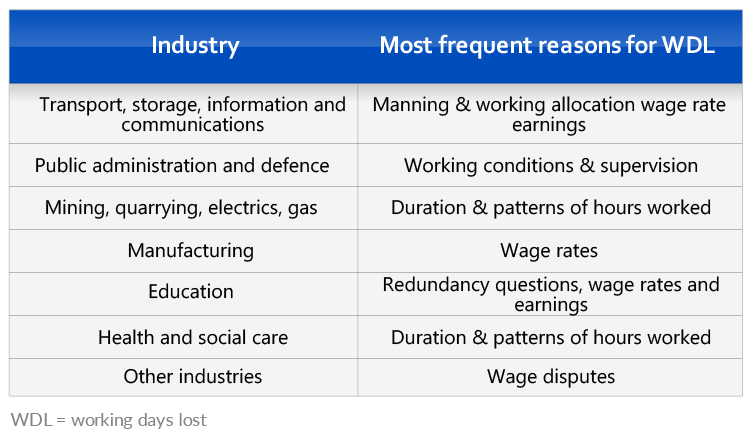

The most common reasons for working days lost through labour disputes include the duration and pattern of hours worked, redundancy questions and wage disputes. Less common reasons include manning and working allocation, working condition and supervision, trade union matters and extra wage and fringe benefits. The table below shows the most frequently reasons for working days lost among industries.

The top 3 industries for striking in 2016 were education, health and social care and transport. Education - 39 per 1,000 employees The wide scale strikes by teachers employees was in part due to an 8% cut in funding in real terms to schools and stagnant wages not increasing with higher workloads. Cuts to support staff and facilities mean that class sizes are increasing and teachers have more to manage. Additionally, schools can now become academies that can decide their own rates of pay and rules. 91.7% of teachers voted in favour of strike action. Health and social care – 33 per 1,000 employees professionals took part in wide-scale striking action in 2016. This was due to a new contract brought in for workers in England, whereby basic pay was increased, yet definitions of what constitutes unsociable hours would change. This would mean Saturdays would be paid the normal rate. Furthermore, pay progression linked to time worked in the job would be changed to several training stages. Transport – 35 per 1,000 employees London has experienced tube strikes for the past 2 years but rail companies have also seen strikes. Reasons for these strikes included 25% cuts to starting salaries, the automation of many jobs which has meant other workers need to work longer hours to make up for it. This includes driverless trains, train support staff and ticket staff At the lower end were construction, technical and administration, information and communications and manufacturing (1-2 per 1,000).

Why is striking so much lower today?

Declining power of trade unions In the 1980’s Margaret Thatcher’s government passed legislation to make it more difficult for workers to legally strike, and memberships of trade unions dwindled as a result. In 2011 numbers of members of the TUC-affiliated Unions were half as many as the peak of 1980. Countries with higher membership numbers such as Denmark and Norway have higher levels of striking in Europe, and some countries have observed numbers increasing, such as Spain, Ireland and Luxembourg. Socio-economic changes Globalisation has led to a more flexible service industry, which has resulted in many working under casual or temporary contracts, which may not fall under a trade union and are harder to regulate. More working regulations Working conditions have improved and become more regulated, Examples being the EU-led initiative of a maximum 48 hour working week (which employers can opt in or out of), health & safety legislation of 1999, establishment of a minimum wage in 1998 and the more recent minimum wage for those aged 25+. Lower confidence The miners strikes of the 1980’s proved ineffective and left thousands unemployed due to the legislation passed by the Conservative government. This led to feelings of disheartenment and confidence in striking plummeted.

Declining power of trade unions In the 1980’s Margaret Thatcher’s government passed legislation to make it more difficult for workers to legally strike, and memberships of trade unions dwindled as a result. In 2011 numbers of members of the TUC-affiliated Unions were half as many as the peak of 1980. Countries with higher membership numbers such as Denmark and Norway have higher levels of striking in Europe, and some countries have observed numbers increasing, such as Spain, Ireland and Luxembourg. Socio-economic changes Globalisation has led to a more flexible service industry, which has resulted in many working under casual or temporary contracts, which may not fall under a trade union and are harder to regulate. More working regulations Working conditions have improved and become more regulated, Examples being the EU-led initiative of a maximum 48 hour working week (which employers can opt in or out of), health & safety legislation of 1999, establishment of a minimum wage in 1998 and the more recent minimum wage for those aged 25+. Lower confidence The miners strikes of the 1980’s proved ineffective and left thousands unemployed due to the legislation passed by the Conservative government. This led to feelings of disheartenment and confidence in striking plummeted.